CROSS CULTURAL – INTERKULTURELL

The Meaning of Adornment: Jewelry in Classical and Hellenistic Attic Vase-painting

Alexis Castor (Lancaster, US)

The expansive iconographic repertoire found on Attic vases would seem to be a valuable source for Greek costume practices. But despite this variety, artists rarely focused on dress details that interest us today. Depictions of jewelry illustrate the point. Painters typically render jewelry as a series of blobs and squiggles set at women’s ears, necks, and wrists. Exceptions occur, of course, but as a rule, vases show accessories only in schematic form. I suggest that the lack of specificity attached to jewelry does not mean that artists discounted the value of the accessories. Vase-painters used jewelry to communicate important messages in ways other than accurate representations of types.

By surveying imagery in which jewelry is prominent – wedding scenes, for example – and also considering scenes in which ornaments are lacking, I shift focus from jewelry as a costume element to a broader consideration of the social meaning of jewelry. Vase-painters highlight jewelry in certain narratives and capture its tactile and visual experience through added clay and gilding. I argue that such enhancements can educate viewers about the value of adornment even if they cannot distinguish specific ornament types.

This study further considers the unexpected prominence of jewelry in Hellenistic black-glaze pottery. Detailed representations of contemporary jewelry, such as strap necklaces, are common motifs on drinking ware and containers; surviving examples of silver vessels show the same embellishments. Greek jewelry styles had become more elaborate in the second half of the fourth century; strap necklaces woven from gold wire and embellished with pendants are one of the new types. Jewelry was placed on the appropriate “body part” of the vase with necklaces encircling the body and wreaths close to the rim. As the only decoration on these vessels, jewelry must serve a new narrative function, communicating a different message. I suggest that jewelry in this medium conveys important notions concerning gender and elite status that developed from its earlier representation in the Classical era.

e-mail: alexis.castor@fandm.edu

Intentional Ambiguity: Cross-cultural Reception in South Italian Vase-Painting

Keely Elizabeth Heuer (New Paltz, US)

Like their Athenian predecessors, South Italian vase-painters were highly adept at distinguishing the mythological subjects in their work through inscriptions and attributes, sometimes including subtle elements such as paidagogos figures to indicate tragedic sources for their visual narratives. However, they also produced a significant amount of imagery for which interpretation of the subject matter is not as transparent, at least to the modern viewer. For example, should the numerous scenes of a male-female pair always be understood as a generic courtship tableau? At times, these couples hold Dionysian objects like thyrsoi and bunches of grapes and may be accompanied by a satyr. In these instances, it is often uncertain whether they were considered to represent mortal devotees of the wine-god or Dionysos himself in the presence of a maenad, nymph, or his consort, Ariadne. Given that South Italian vases are uncovered overwhelmingly in tombs, should these figures perhaps be recognized as the deceased themselves?

Even more enigmatic are the thousands of isolated heads of various types, predominantly female, that served as primary and secondary decoration on over one-third of the surviving corpus of South Italian vases. Relatively few examples have conclusive identifying attributes and in only one instance, on the neck of a volute-krater now in the British Museum, the head is inscribed, given the curious name of “Aura” (“Breeze”). South Italian vase painters’ repeated use of seemingly ambiguous iconography can be explained by one of two plausible scenarios: either the meaning of the imagery was so obvious to its ancient audience that standard identifying cues were deemed unnecessary or its vagueness was intentional. Considering that South Italian vases were produced not only for Greeks living in the settlements along the coastlines of Magna Graecia and Sicily but even more so for their indigenous neighbors, I propose that South Italian vase painters cleverly recognized the communicative effectiveness of ambiguity in producing imagery with universal appeal due to its flexibility of interpretation dependent upon the viewer’s ethnic and religious background.

e-mail: heuerk@newpaltz.edu

Images, Inscriptions, and a Repair: Beazley’s Epelion Painter in Italy and Beyond

Thomas Mannack (Oxford, GB)

Athenian vase-painters endeavoured to produce scenes which appealed to as many different customers as possible. The Epeleios Painter and his circle decorated mainly cups in the early 5th century BC. Beazley derided their paintings as Schmiererei, but their vases nevertheless attracted buyers on the shores of the Black Sea, in Thasos, Athens, where their cups were dedicated on the Acropolis and used in the Agora, Etruria, and perhaps beyond, since repairs on a cup fragment once on the Roman art market suggest that it was bought by a prince of the Hallstatt culture. The appeal of the workshop’s cups lay in the shape, which suggested that the owner was part of the symposium class, and the relentlessly cheerful scenes of symposia, komasts, athletes, and warriors, which implied a Greek aristocratic lifestyle too. A few of the mythological scenes appear to have a special Athenian flavour as they juxtapose the hero of the Archaic period, Herakles, with the new hero of the democratic age, Theseus, but both would have been popular choices for Etruscan graves because they personified exemplary lives and both escaped death.

Numerous inscriptions, some just scribbled words, some proper kalos inscriptions, must have added to the attraction overseas as a second sophisticated layer of decoration, especially in Etruria: all the workshop’s vessels praising Athenians by name have been found there and probably identified the buyers as cultured individuals partaking in Greek culture. The named males, just like the individual styles, show that the Epeleios Painter and his fellows were closely linked to other Athenian cup painters of the period.

e-mail: thomas.mannack@beazley.ox.ac.uk

Unexpected Signs in Unexpected Contexts: Meaningful Relationships Between the Apotheosis of Herakles and the Apobates Race in Athenian Vase-painting

Diana Rodriguez Perez (Oxford, GB)

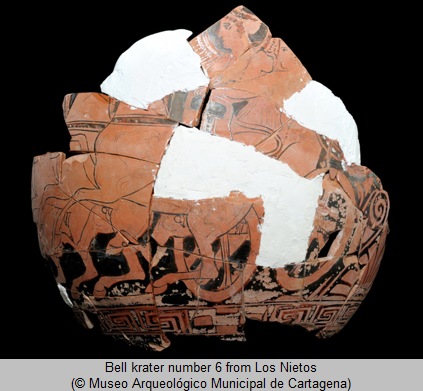

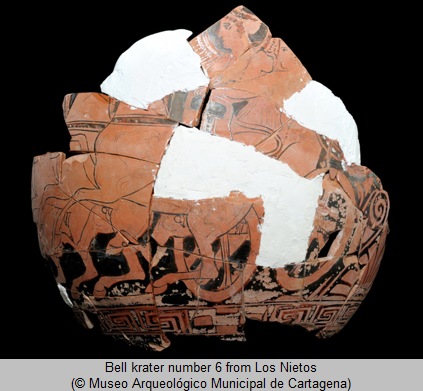

In my contribution I shall explore the relationship between the images of the apotheosis of Herakles and the apobates race in relation to a 4th century Athenian bell krater from La Loma del Escorial de Los Nietos (Cartagena, Spain).

Both iconographies, the apotheosis of Herakles and the apobates race, show remarkable compositional similitudes from the end of the 5th century onwards that are suggestive of an assimilation at the level of meaning, in particular in the peripheral areas of the Greek world. There is an interesting exchange of signs between both scenes at that time, which shall be considered together with the roughly later scenes of Nike driving a chariot and the related Nike (or Nike-like) iconography in the Iberian Pensinsula. The analysis of these scenes as part of the wider visual system of Greek iconography sheds light on the ways in which images and iconographic types acquire meaning as well as on the kind of images favoured by the final users of these vases in the Peninsula — the Iberians.

e-mail: diana.rodperez@gmail.com

Translating Foreign Tongues: Understanding Attic Pottery in Context at the North Etruscan Sanctuary at Poggio Colla

Ann Steiner (Lancaster, US)

What Athenian and Athenian-inspired vases communicated to their Etruscan audience has become a fertile topic of scholarly discourse, particularly in the past fifteen years. The use-contexts of Athenian red-figure vases in Etruscan settings surely affected the messages they communicated. For evidence excavated from tombs, we see the grave itself as well as the full spectrum of grave goods with which Athenian pottery interacts; the context as a whole then communicates social messages about ethnicity, gender, and status. The focus here turns to interpreting the messages of Attic and Atticizing ceramics in a religious context, at the North Etruscan sanctuary at Poggio Colla, 35 kilometers northeast of Florence.

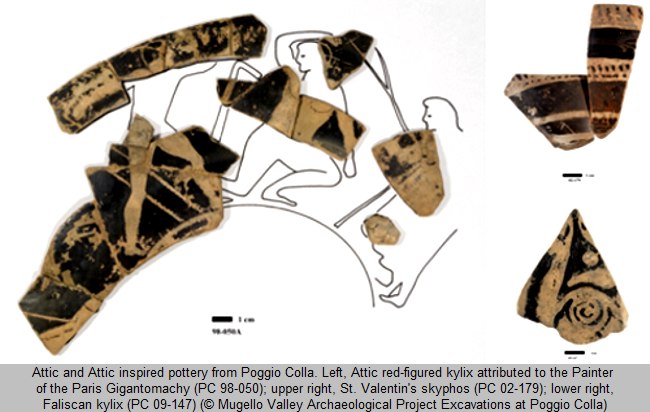

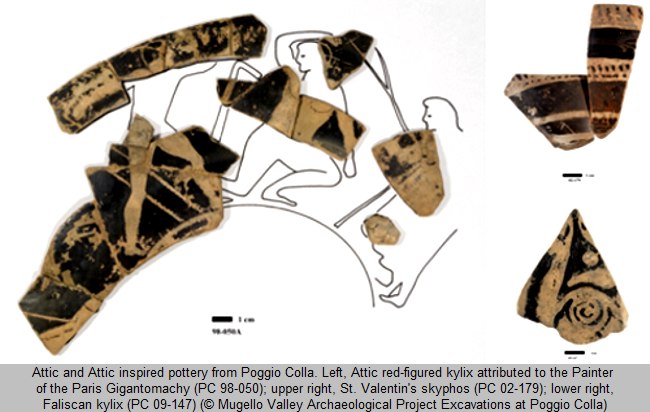

At Poggio Colla, Attic red-figure imports in the 5th and 4th centuries are extremely rare. They stand out dramatically among local fine wares and dedications of luxury objects, including gold jewelry and bronze statuettes. This study includes three small case studies involving pottery produced over a century: 1) a red-figure kylix by the Painter of the Paris Gigantomachy (c. 475 B.C.), found in conjunction with religious activity at the first monumental stone temple; 2) a St. Valentin’s skyphos (c. 425–400 B.C.) integrated within an extensive bronze stipe votiva; and 3) a Faliscan red-figure kylix (c. 350–325 B.C.), a production at first highly Atticizing and later more wholly Etruscan, as part of an extensive context, filled with commensal black gloss and fine ware and other votive material from a 4th century phase of the sanctuary’s history.

The first example contrasts with the undecorated late bucchero vessels that share its context. The Early Classical athletes that decorate the kylix are the only human figures to appear on any ceramic evidence for this period at the site; contemporaneous bronze figurines of male and female figures are highly archaizing as are the antefixes of the temple. The St. Valentin’s skyphos lacks human figures, but is the only painted pottery in an extensive deposit of intentionally-broken bronze votives including both animal and human figures. Finally, both shape and decoration of the Faliscan kylix contrast with significant quantities of gendered drinking ware decorated with stylized vegetation on skyphoi sovradipinti and stamped patterns on black gloss kylikes.

In each case, the Attic or Attic-inspired vessel is a striking anomaly, differing in unique ways from the material culture surrounding it, thus making more potent the messages it communicates. Collectively, these examples, stretching over nearly a century, reveal some of the crucial information context can provide for understanding the full measure of Athenian vases as a medium of communication.

e-mail: ann.steiner@fandm.edu

„Herrenlose“ Gegenstände auf unteritalischen Vasen

Cornelia Weber-Lehmann (Bochum, DE)

Auf apulischen Vasen erscheinen etwa ab der Mitte des 4.Jhs. in komplexen Szenen verschiedenen Inhalts (Mythen, Naiskos etc.) Antiquaria in stark kanonisierter Form und in zahllosen Wiederholungen. Diese Gegenstände (etwa Fächer, Musikinstrumente, Hydrien, Spiegel u.v.m.) werden oft in den Händen von Figuren gehalten und daher zunächst als Attribute wahrgenommen, die die jeweilige Figur oder ihre Situation kenntlich machen bzw. unterstreichen. Immer öfter finden wir sie aber auch wie vergessen oder liegen geblieben am Boden, halb von Felsen verdeckt oder in der Luft schwebend. Es scheint, als seien die Gegenstände zu selbstständigen Chiffren geworden, die durch ihre Lage und Anbringung im Bild ganz bestimmte Inhalte kommunizieren können und damit den Hintergrund zum Verständnis des Geschehens liefern. Während beim antiken Betrachter die Kenntnis dieser Zusammenhänge offensichtlich vorausgesetzt werden konnte, finden sich in der modernen Forschung nur selten Versuche, diese ‚Botschaften‘ zu entschlüsseln. In dem Beitrag sollen Beispiele gegeben werden, die zeigen, dass es durchaus lohnend ist, sich auf diese ‚Kommunikation der Gegenstände‘ näher einzulassen.

e-mail: cornelia.weber-lehmann@ruhr-uni-bochum.de

This article should be cited like this: C. Lang-Auinger - E. Trinkl, Griechische Vasen als Kommunikationsmedium / Greek Vases as Medium of Communication, Forum Archaeologiae 84/IX/2017 (http://farch.net).