Sonia Klinger, Haifa

Fauna in the World of Women in Ancient Greece. Some Questions

Evidence for fauna in the world of women in ancient Greece derives from different sources: artifacts, textual references, and iconographic and contextual evidence. The best known type of evidence is provided by Attic vase-painting scenes linking women with animals. These case studies, based on visual and textual sources, allow us to understand the reasons for the animals’ presence next to women and their paradigmatic meanings in the scenes.

Amid these case studies are those of women with birds, such as the 1987 discussion of women with herons by Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood; the 1997 and 2002 studies by Elke Böhr exploring the link between women and wrynecks, and between women and demoiselle cranes; the 1998 and 2008 studies on women and geese by Alexandra Villing and myself; and the 2003 study of women with rock partridges or Greek partridges by Aliki Kauffmann-Samaras.

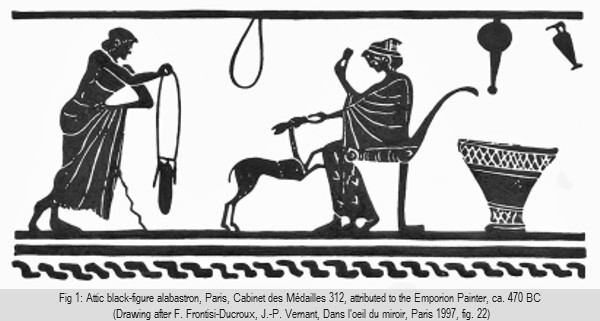

Well known are also scenes linking women with deer (fig. 1) studied and published by myself in 2002 and 2009. Other cases linking women with animals remain unexplored. One example is the current study of women with bees pursued by Nitzan Levin in her forthcoming doctoral dissertation at the University of Haifa.

Die Verhaltensforscher Erik Zimen und Dorit Petersen-Feddersen haben in den letzten 20 Jahren Untersuchungen an Haushunden sowie halbwilden Caniden (Dingos und Wölfen) unternommen und herausgefunden, dass Hunde im Laufe ihrer Domestikation einen besonderen Verhaltenskodex im Umgang mit den Menschen erlernt haben. Dieser Verhaltenskodex wurde vermutlich bis in die Gegenwart unbewusst vom Menschen weitergezüchtet.

Für die ikonographische Auseinandersetzung und Betrachtung der antiken Vasenbilder ergeben sich für meine Arbeit mehrere Fragen, welche im Vortrag eine Beantwortung finden sollen:

This vase bears witness to an unprecedented unity of theme, in a Brygan context, between moulded shape and figural decoration in its well-considered and wholly satisfying marriage of animal’s hoof to bowl’s vivid snapshot of animal husbandry, one of the manifold human spheres overseen by Hermes. And given the intimate relationship of Hermes to Dionysus, god of wine, the choice of subject here for a drinking cup takes on added appropriateness for the celebration, perhaps, of both divinities in unison, overtly or subliminally, in a sympotic context. Brief mention will here be made, by way of contrast, of the various shapes and decorative schemes of selected Brygan rhyta. In addition, in light of the natural continuum of vine, wine cultivation and the countryside, notice will be taken of the Brygos Painter’s splendid out-of-doors depiction on drinking cups of Hermes, innocently lying swaddled in a liknon at cave’s mouth, and the cattle of Apollo. Lastly, a further and unusual testament to the linkage of the realms of Hermes and Dionysus is provided by a cup of the same date, ca. 470 BC, by a member of the Pistoxenan Group, the Ancona Painter, on whose exterior is depicted the diminutive figure of a bearded shepherd, in garb similar to that of the Met’s cowherd, who, from his perch atop a tall hillock, concealed behind branches, spies upon a relatively controlled revel of maenads and satyrs in the presence of Dionysus.

This paper proposes that the detail can be identified as one which Xenophon advised to be observed in order to verify the good health of horses. In his treatise on the horse (Peri Hippikes XI, 2), written around 360 BC, the historian speaks of the area he calls the keneon and recommends to assess its condition. It corresponds to the soft area between the rib cage and the hind leg, where some fat often accumulates, and where the hair grows out in a whorl: its good condition reveals the state of health and the quality of a steed. The appearance of this detail in the iconography of Athenian vase-painting at the turn of the 6

© Heide Mommsen

A second type of evidence that sheds light on the fauna linked to the world of women are the artifacts found in sanctuaries associated with female activity. One representative example, due to its connection to females, issues of fertility, the household and the central well-being of the family, is the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at ancient Corinth.

My work toward the publication of the sanctuary’s minor finds allows me the opportunity to present in this paper some of these artifacts and compare the evidence they offer with that provided by the Attic vase-painting scenes linking women with animals. I also aim to examine the possible implications resulting from these comparisons in terms of meaning, function and locality and shed some light on the art alluding to fauna in the world of women in ancient Greece, its uses and incidence.

© Sonia Klinger

e-mail: klinger@research.haifa.ac.il

Isabell Algrain, Brüssel

Isabell Algrain, Brüssel

"À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur". Women and Flowers on Attic Pottery

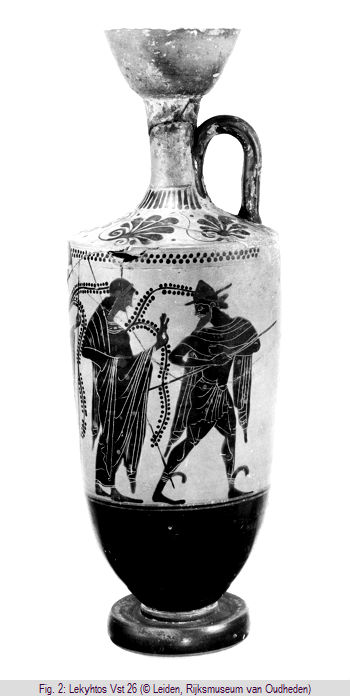

A great number of Athenian vases of the Archaic and Classical periods bear representations of women holding a flower in their hands (fig. 2). These women appear in different contexts, sometimes as the central character in a scene, sometimes as a mere spectator. The woman holding a flower is depicted in scenes of water fetching, rituals at altar and domestic contexts. In courtship scenes a man sometimes offers a flower to a woman. Yet, the relationship between women and flowers in Attic pottery is not only made by the way of the iconography, but also with inscriptions: the inscriptions identifying women on Attic pottery often give them «flower names» such as Rhodon, Elanthis, Anthylè or Rodopis.

The purpose of this article is to question the meaning of the flower held by these women and to see if the interpretation of this iconographic element may vary depending on the context in which it is represented. The flower may be interpreted in various ways such as a symbol for perfume (which could not be expressed in any other way in art) or as a more complex metaphor for young women. Other questions may also arise. Are women who hold or receive a flower as a gift honorable women or hetaira? Does the flower only characterize nubile girls to get married or married women? We will thus also try to determine if this flower may be used as a way to determine the social status or the age of women portrayed with this attribute.

© Isabell Algrain

e-mail: ialgrain@gmail.com

Beatrice Franke, Hamburg

Die Darstellung der Kommunikation zwischen Mensch und Tier auf griechischen Vasen

Der Vortrag befasst sich – basierend auf einer ikonographischen Betrachtung der attisch- schwarzfigurigen und rotfigurigen Vasenmalerei des 6. bis 4. Jahrhunderts v.Chr. – mit der Darstellung der Kommunikation zwischen Mensch und Tier auf griechischen Vasen. Im Vordergrund steht die Mensch-Tier-Beziehung in der griechischen Gesellschaft, die sich nicht nur auf die Evaluation der Vasenmalerei beschränkt, sondern auch die soziokulturellen Aspekte analysiert.

Das antike Bildmaterial wird nach Themen gegliedert und methodisch in eine aktive und passive Mensch-Tier-Beziehung eingeteilt. Diese Vorgehensweise soll helfen herauszufinden, welche Funktion und Stellung das Tier neben dem Menschen in der Antike einnahm.

Eine aktive Beziehung bedeutet, dass das Tier vom Menschen direkt und zielbewusst angesprochen wird. Die Ansprache wird hier in Form von Gesten als kommunikatives Mittel verstanden. Eine Bindung zwischen Mensch und Tier ist deutlich gegeben. Eine passive Beziehung bedeutet, dass das Tier sich in einer vom Menschen nicht angesprochenen Kommunikation, aber in einer feststehenden Bindung zu ihm befindet. Das heißt, das Tier befindet sich in der Nähe des Menschen bzw. in einem geringen Einzugsbereich, jedoch wird zwischen Mensch und Tier keine aktive Kommunikation erkennbar, die gezielt vom Menschen ausgeht.

Allein die Choenkännchen mit den Kinderabbildungen im Spiel mit Tieren oder die Darstellungen der jungen Heranwachsenden in Begleitung ihrer kleinen spitzartigen Haushunde, aber auch Abbildungen der Jagdhunde im Beisein von Gelagen oder Jagdausflügen erwachsener Männer, zeugen von einer bemerkenswerten Natur-, Tier- und Verhaltensbeobachtung der Griechen.

Zu einer Beziehung gehört immer die Kommunikation (Abb. 3), als ein wesentlicher Bestandteil der Bindung zwischen zwei bzw. mehreren Individuen. Menschen wie Tiere kommunizieren durch ihr Verhalten zueinander. Das heißt, durch ihre Körpersprache (Gesten und Mimik) sowie durch Stimmen und Geräusche. Vor allem Tiere, die in Gruppen bzw. Familien-verbänden leben, besitzen ein ausgeprägtes bis hin zu einem nuancierten Sozialverhalten. Zu diesen Tierarten zählen vor allem Hunde. Der Hund in allen seinen Rassenvariationen ist eine Kulturleistung und stellt bis in die Gegenwart ein lebendiges kulturelles Erbe dar. Dieses ist über Jahrtausende und durch verschiedene Kulturen zurückzuverfolgen.

1. In welchem sozialen Kontext kommen domestizierte bzw. auch gezähmte Tiere in der griechischen Gesellschaft vor?

2. Wie wird das Tier verstanden, bzw. welche soziale Rolle kommt ihm im Zusammenleben mit dem Menschen in einer Gesellschaft zu?

3. Wie kann die Kommunikation in Form der Verbildlichung für einen dritten Beobachter verstanden werden?

4. Folglich, gibt es Kommunikationsmuster auf griechischen Vasen? Wenn ja welche und wie sehen diese aus?

© Beatrice Franke

e-mail: saegemuellerin@yahoo.de

J. Robert Guy, Basel

From Head to Hoof: Brygan Plastic Vases, Late Archaic to Early Classical

This paper proposes to highlight a charming and relatively little-known Attic vase in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum, New York – a small, one-handled drinking vessel that is exceptional, indeed unique, both in its shape and in its scheme of decoration. Acquired in 1938, and first published soon thereafter by Gisela Richter, it is a plastic cup in the form of a cow’s hoof (fig. 4). The realistic body of the vessel, fashioned in a mould, is surmounted by a wheel-thrown bowl, across the surface of which unfolds continuously a delightful visual „pastorale“. In a bucolic landscape of cave-opening accented with ivy, tree and shrub, a young cowherd, seated at ease on a rocky outcrop, tends to two of his charges in the company of hound and hare. Richter wrote: „The unusual shape and subject suggest the Sotades Painter. But the hand is not his“. Beazley did not hazard an attribution. On the basis of style of drawing and ornament, however, this vignette of rural life may with confidence be attributed to a member of the large and fruitful Brygan workshop, perhaps more closely to an artist of the Mild Brygan Group whose career, together with those of several of his related fellows, successfully spans the transitional years from the late archaic to the early classical period, thereby keeping alive, and leading to their revitalization in the hands of the next generation, two notable elements of Brygan production – plastic vases, principally animal’s head rhyta, and white-ground cups.

© J. Robert Guy

e-mail: robert.guy@cahn.ch

Mario Iozzo, Florenz

Xenophon, Peri Hippikes XI, 2 and the Flank of the Horses

In recent years, many studies have dealt with the horse and its iconography in ancient Greece. One detail of horse anatomy, however, has never been explained, despite the fact that it appears very frequently on red-figured vases beginning in the late 6

© Mario Iozzo

e-mail: mario.iozzo@beniculturali.it

Nitzan Levin, Haifa

Bees as Shield Device on Greek Vase-Painting

The importance of bees and their role in ancient Greek culture are well known to us from various ancient sources. Different myths connect bees and their products to major Greek gods, and their general perception is chiefly positive. They appear in various very early myths, and although their meaning is often obscure, they seem to be related to all aspects of life and death, from everyday custom to religious rituals and cults.

The subject was explored by various scholars. Notably among them is Arthur Cook’s 1895 article on the bee in Greek mythology; Hilda Ransome’s 1937 study discussing the cultural role of the bee; Eva Crane’s life work on the history of beekeeping; Malcolm Davies’ and Jeyaraney Kathirithamby’s important investigation of Greek insects from 1986; and Marco Giuman’s recent discussion on bees and women.

Ancient sources, such as Vergil’s Georgica, connect bees to different aspects of death and rebirth. This notion relates to the belief in reincarnation of the dead souls as bees and their journey to the underworld. It also relates to their close connection with chthonic gods and to the actual finding of bee-related images, including beehives, in funeral contexts. Moreover, their honey was known through ritual libation as a miracle substance with mediatory power which was also used for embalming and preserving bodies. The bee itself was used as a protecting emblem against death and the "evil eye".

This paper will focus on an interesting group of Attic vase-paintings with warriors holding shields portraying bees on departure scenes, marching into battle and fighting. Examination of textual and visual materials related to the concept of the bee in the ancient Greek world will allow me to argue that the use of bees as shield-devices alludes to their apotropaic capabilities, offering protection and averting harm, defending against the evil eye, paralyzing the enemy and guarding the life of the shield carrier, a role similar to that of the more common Gorgoneion. This role as shield-devices also alludes to a previously unnoticed connection between bees and the male world. The location of the bees as shield-devices on the vases may indicate the family’s desire to provide some kind of protection to their loved ones or to commemorate a fallen relative. In cases where the vases are found in burials the bees decorating shields may acquire a symbolic meaning alluding to the embodiment of the person’s soul through bees, his revival and rebirth.

© Nitzan Levin

e-mail: nitzanlevin@hotmail.com

Anne Mackay, Auckland

Figures of Comparison. A Study of the Potential for Animal and Bird ‘Similes’ in Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painting

On many Attic black-figure vases, animals and birds are either included in the scene or juxtaposed in an adjacent zone. This paper will explore the potential for interpreting at least some of them as providing an additional lamination of meaning that often serves an adverbial function: commenting on how the action of the main scene was performed, for instance. It will be proposed that this is a system of meaning construction that is predicated upon the existence of a substantial corpus of folk-comparisons, and that it works in parallel to the process of iconographical meaning generation, so extending a communicative approach that is fundamental to the black-figure technique and central within the traditional repertoire of picture elements in the archaic period. The effect of these images will be compared with that of the familiar similes of traditional oral or oral-derived epic.

© Anne Mackay

e-mail: anne.mackay@auckland.ac.nz

Heide Mommsen, Stuttgart

Pferde bei Exekias

Pferdebilder sind im Werk des Exekias auffallend häufig und ungewöhnlich vielseitig. Leicht übersieht man bei diesem Maler, was neu und daher von besonderer Bedeutung ist, da es in der Folgezeit schnell zum Allgemeingut wird. Auch seine Pferdebilder sind voller Erfindungen, die ein lebendiges Interesse des Exekias an ungewöhnlichen Ansichten und dramatischen Situationen bekunden, oder auch eine besondere Aussage übermitteln.

Unter dem Aspekt des Neuen und Besonderen sowie dessen Auswirkungen im Kerameikos soll ein Überblick über die Pferdethemen des Exekias gegeben werden. Die ruhig stehenden Viergespanne, die bei verschiedenen Themen das Bild beherrschen, sind dabei ausgenommen. Anschirrungsszenen sind vor Exekias nur einmal auf dem Nearchos-Kantharos (ABV 82.1) überliefert, wo das Gespann des Achill zum entscheidenden Kampftag angespannt wird. Diese Anschirrung hat Exekias auf den Fragmenten der Sammlung Cahn (HC 300) übernommen, aber in neuer Komposition, wobei er das Thema auf beide Seiten des Gefäßes verteilt; ebenso teilt er die Szene bei seinen anderen beiden Anschirrungen, bei denen der ausfahrende Krieger unbenannt bleibt. Bei beiden bringt er bewegte Pferde ins Bild: auf der Amphora in Boston (Mackay 1) scheut eines der Pferde und muss beruhigt werden, auf der Amphora in Zürich, Privatbesitz (Mackay 22) geraten drei Pferde während der Anschirrung in beängstigender Weise in Panik und drohen ›durchzugehen‹. Die Beliebtheit der Anschirrungsszenen in der Folgezeit geht auf die Vorbilder des Exekias zurück, wobei allerdings die gefährlichen Zwischenfälle weggelassen werden.

Das stürzende Gespann mit einem Pferd in Unteransicht auf einer weiteren Amphora in Züricher Privatbesitz (Mackay 23) vertritt wieder das besondere Interesse an heiklen Situationen und anspruchsvollen Ansichten, für die es keine Bildtradition gibt. Für diese Neigung zeugt auch die Amphora im Louvre (Mackay 7) mit ihrer ungewöhnlichen Kampfdarstellung zwischen Hopliten und zwei berittenen Bogenschützen, deren eines Pferd gerade stürzt, während das andere scheut.

Im Gegensatz zu diesen bewegten und bedrohlichen Pferdeszenen stehen einige ruhige und gedankenvolle Bilder mit einem oder zwei Pferden, die geführt werden. Das Motiv des Pferdeführers ist in der ersten Hälfte des 6. Jahrhunderts äußerst selten, wird aber von Exekias auf der Amphora Berlin F 1720 (Mackay 11, Abb. 6) und auf der Vatikanamphora (Mackay 32) sehr auffallend in Szene gesetzt. Wenn Kastor bei seiner Heimkehr ins Elternhaus sein Pferd mit sich führt, ist das nicht befremdend, da die Dioskuren die bedeutendsten Reiterheroen sind. Die Szene mit Akamas und Demophon wird gewöhnlich als deren Aufbruch zum trojanischen Krieg gedeutet, wofür jedoch ein Streitwagen angemessen wäre. Das Motiv des Pferdeführens soll in diesem Fall als eine Angleichung an die Dioskuren und damit als Zeichen für die besondere Bedeutung der Theseussöhne als attische Heroen interpretiert werden. Die Rückseiten der Anschirrungsszenen, wo ein oder zwei Beipferde herbeigeführt werden, gehören, für sich genommen, auch zu den ruhigen Bildern mit Pferdeführern; es sind die Vorbilder für zahllose Kriegerabschiedsszenen der Folgezeit. Rätselhaft und ohne Nachfolge bleiben die Darstellungen der Amphora in Philadelphia (Mackay 24), auf der in jedem Bildfeld ein Krieger sein Pferd grasen lässt, auf der einen Seite ist es ein Hoplit, auf der anderen ein frühes Beispiel eines Bogenschützen in ›skythischer‹ Tracht.

e-mail: heide.mommsen@t-online.de

![]()

This article should be cited like this: ΦΥΤΑ ΚΑΙ ΖΩΙΑ / Abstracts: Pflanzen und Tiere in Alltagsszenen, Forum Archaeologiae 68/IX/2013 (http://farch.net).