The gold vessel in question was confiscated by German customs from a Munich auction house in September 2005 at the request of the author and transferred to the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum in Mainz for scientific inspection and safe keeping. The vessel had been sold without provenance and without the appropriate legal documents from its country of origin. According to expert opinion as provided by the author to the Customs authorities, the vessel was not, as maintained by the auction house, a 2000 year old product of the Roman era. Instead it was made 4500 years ago by a Sumerian craftsman in Mesopotamia and is one of the oldest gold vessels ever to be discovered. Most probably it originates from a looted royal tomb in southern Iraq.

Recently the buyer of the gold vessel, a lawyer and top manager of a global corporation with mayor operations also in Iraq, announced that he wished to return the vessel to the Iraqi authorities - being a collector, not a fence. This realization occurred to him when the Iraqi cultural attaché called in January of this year. The jurist had acquired the gold vessel four years earlier for 1200 €, despite the proviso under which it was auctioned due to the Iraqi property claims. In a letter to Customs he had required that the gold vessel be surrendered to him. Of course he would denounce the looting of archaeological sites in principle but Customs were obliged to provide evidence to him that this very gold vessel derived from such lootings. This letter put the Iraqi embassy, which had access to the records due to being actively involved in the proceedings, onto his trail.

Antiquities found in Iraq are, as a rule, public property of the Republic of Iraq unless an exception can be plausibly demonstrated (for example by an Iraqi export licence). According to German law, selling and buying Iraqi antiquities as a rule constitutes a criminal offence: In addition to the criminal offence of receiving and selling stolen goods as a rule it also violates the embargo provisions of Article 3 of the Council Regulation 1210/2003 of the European Union. § 34 Außenwirtschaftsgesetz, the German Foreign Trade Law, punishes this offence with imprisonment for anything up to five years.

So much for the theory - the jurisdictional reality is somewhat different. On June 3rd, 2009 the auction house obtained an order from the Fiscal Court in Munich, obliging the Customs authorities to physically hand over the gold vessel to the court "for inspection". Consequently Customs demanded the return of the gold vessel from the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum. At this point the Munich Public Prosecutor's office had already closed its investigations despite the fact that neither legitimizing documents nor the evidence required under EU regulations could be presented. Customs communicated to the author that it would return the gold vessel to the auction house if the Fiscal Court were to rule that, on formal grounds, Customs had acted without authority when confiscating the vessel.

This announcement fitted flawlessly into the ignominious tradition of trade friendly decisions by German law enforcement authorities. For example, on June 24th 2008 the Landgericht München, the Munich Regional Court, ruled that confiscated Turkish antiquities be returned to the auction house: ", dass bei einer Güterabwägung zwischen den berechtigten Interesse der Republik Türkei an dem Erhalt ihres Kulturgutes und dem Recht der Gewahrsamsinhaber an der Verwertung ihrer Gegenstände letzteren Interessen der Vorzug zu geben ist" ("that on weighing up the legitimate interests of the Republic of Turkey in preserving her cultural heritage against the right of the bailee [i.e. the auction house] to commercialize his goods, the latter should be given priority.")

The author was left facing the dilemma that, on the one hand, as an official of a public institution, he was obliged to obey the decision of a German court. On the other hand, by removing the gold vessel from the vaults of the museum, he would possibly pave the way for continuing abuse of the gold vessel by illegal trading. The problem boiled down to the following question: Could a public institution like the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum be forced by another public institution, in this instance Customs, to collaborate in criminal actions?

Additionally, the Iraqi ambassador had explicitly urged the author not to remove the gold vessel from safekeeping until the court of highest instance had ruled on the rights of ownership. He feared that returning the vessel to the auction house would prevent its real owner - the Republic of Iraq - claiming back its property in accordance with the rules of law.

The author therefore advocated an amicable solution and proposed that this "inspection by the court" should take place within the compound of the museum in Mainz. This proposal caused considerable irritation, culminating in an announcement by Customs that they would come to Mainz and take the gold vessel by force - if necessary using a welding torch to open the safe. Due to the tremendous media hype - seven television broadcasting companies had announced they would cover the welding drama - the collection date was postponed three times at short notice. At the fourth attempt the gold vessel was handed over to Customs "voluntarily".

A second expert opinion, commissioned by the court, confirmed my findings and on September 25th 2009 the Fiscal Court in Munich ruled that the gold vessel was of Iraqi origin. Revision was not permitted. The auction house lodged an appeal against this ruling.

Even if the only acceptable solution - returning the gold vessel to its true owner, the National Museum in Baghdad - is now apparently under way, the case itself is far from being solved. The exact location where the gold vessel was found is still unknown. The illegal networks are still intact and further important antiquities from the same presumed royal tomb, among which are objects of gold and silver have, to date, not been confiscated. Despite repeated requests by the author, the law enforcement authorities felt they were not in the position to do so.

At least the burial gifts rooted out of the grave by the looters should be secured. The invaluable information which was destroyed during the undocumented pillaging of the location is in any case lost forever. The last time untouched royal burials were discovered and excavated by archaeologists in Iraq was more than eighty years ago (in the Royal Cemetery of Ur).

This case is symptomatic for the handling of antiquities of dubious provenance. Without the public outrage - and the courageous commitment of an Iraqi ambassador and cultural attaché - the gold vessel would probably have been returned to the presumed fence. If in the past investigations and confiscations have occurred at all, this was usually the result. Dealers in antiquities have excellent and well paid lawyers at their command.

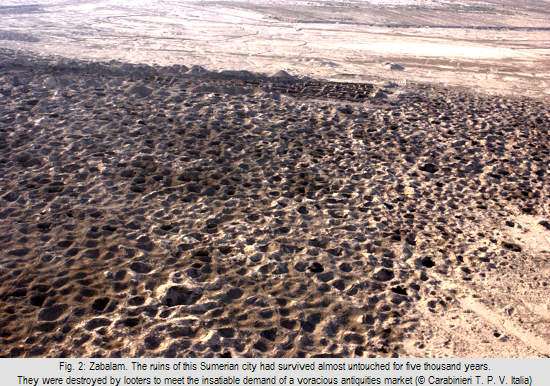

The market for archaeological objects of unknown provenance provides the financial incentive for the looting of archaeological sites, causing undocumented destruction of the information saved in the ground. Acquiring "unprovenanced" antiquities means acquiring responsibility, not only for the very looter's pit from which the trophy was plundered but also for the additional future destruction which will be financed with this money.

In view of these facts, professional associations like the International Council of Museums (ICOM) or associations of art dealers have issued codes of professional conduct, forbidding their members to acquire or sell antiquities of illegal origin.

However, these apparently apply only in theory: Again, real life is somewhat different: UNESCO and the FBI estimate the volume of the illegal trade in antiquities at 6 to 8 billion USD per year. Along with drugs, weapons and trafficking in human beings the antiquities trade is among the illegal businesses with the highest turnover. In view of these profits even battalions of site guards would prove futile. In a market economy supply is determined by demand. Therefore combating the trade in looted antiquities is vital for the protection of archaeological sites.

A new way of thinking has to take place, particularly on the side of law enforcement authorities. Here the shortcomings arise from an underestimation of the destructive character of the market for unprovenanced antiquities, which leads to illegal diggings and destruction of archaeological sites. The failure to fulfil their duties is based on a misconception about the basic facts of the case and of determining the rule.

The presumed legal origin of unprovenanced antiquities and their supposed marketability are pure fiction and have nothing to do with reality: Antiquities, offered without comprehensive designation of origin and without valid documents issued by the country of the place of discovery are, as a rule, of illegal origin.

This can be demonstrated by the following facts:

1. Archaeological finds of legal origin always have a place of discovery. However, for antiquities of illegal origin, this information is being faked or concealed in order to avoid prosecution and claims from the true owner.

2. All countries with vestiges of ancient civilisations have strict legislation concerning archaeological finds. Antiquities are always affected by restrictions concerning acquisition of ownership and export. In order to protect their archaeological sites, most countries have declared cultural assets from their territory as public property. Even in those countries which do not yet vest ownership in the state, antiquities are not ownerless. These countries at least practise Hadrian's division; i.e. the discoverer acquires ownership only of one half of the find. The other half belongs to the owner of the place of discovery.

3. Should ownership and export be possible at all, such instances always generate official documents. Therefore, antiquities of legal origin are, as a rule, equipped with valid documents from their country of discovery.

4. Good faith acquisition without comprehensive documentation of legal origin is not possible. If you buy a passport at a flea market, you will not have acquired ownership in good faith since everybody knows that passports are the property of the country of origin. The same applies to antiquities: You can only remain ignorant about the restrictions concerning acquisition of ownership and export either deliberately or through gross negligence. These restrictions have existed for many generations: Hadrian's division for two thousand years, the ban on exports of antiquities from Greece for example since 1834, from the Ottoman Empire and its successor states like Iraq since 1869 and from Iran since 1930. A potential buyer must know that an illegal origin is more than likely if the aforementioned documents are missing. In particular this applies to dealers who make a living from selling objects which are regularly affected by such restrictions.

5. Other ways of acquiring ownership, based on good faith acquisition: to acquire by possession or through public auction are therefore also not possible.

6. The presumption of ownership is disproved by the absence of documents with which antiquities of legal origin are regularly accompanied.

Who claims the exception from the rule, carries the burden of proof.![]() © Michael Müller-Karpe

© Michael Müller-Karpe

e-mail: muellerkarpe@rgzm.de

This article should be cited like this: M. Müller-Karpe, Archaeologists in Conflict: To Buy or not to Buy. The Sumerian Gold Vessel from Munich, a Case Study for Dealing with Unprovenanced Antiquities, Forum Archaeologiae 56/IX/2010 (http://farch.net).