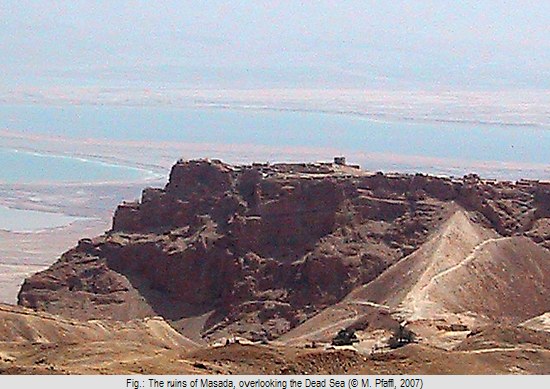

As astonishingly as the architectural value of the fortress may be, it mostly drew attention in a completely different context.

These "sicarii" had occupied Masada in 66 CE and held the fortress until 73 CE, when Silva's tenth Legion, after months of a futile siege, entered Masada via a giant siege ramp. The rebels, that had women and children among them, faced a grim future: Either enslavement or dead by crucification. Thus the rebel's leader, Eleazar Ben-Yair, held a charismatic speech, as transcribed by Josephus Flavius, that suggested mass suicide as a means to avoid Roman cruelty. Subsequently nearly all of the 960 inhabitants of Masada ended their life and burnt their belongings so the Romans could find nothing of use.

As deeply moved as Shmaria Guttman was by Josephus Flavius narrative, as little interest did his contemporaries show. Even a man like Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, head of the Jewish national committee at that time showed little interest in the place: 'Why are you so excited? Masada? Nine hundred Jewish robbers run from Jerusalem to Masada and committed suicide. So what? What is this excitement all about?' was all he would say to Guttman.

It was only in the beginning 1960ies that Guttman found a powerful ally: Hebrew University of Jerusalem's archaeologist Yigael Yadin, a former high ranking officer of both the Jewish underground army HaGanah and the Israel Defense Forces.

From 1963 to 1965 Yigael Yadin conducted excavations at Masada, supported by means of personnel, funding and equipment by a vast number of national and international Jewish organizations, as well as the Israeli army.

It was the beginning of the rise of the Masada Myth. The story that had been passed down by Josephus Flavius was, without the necessary criticism of sources, taken as face value, if not exaggerated, into the narrative of the heroic last stand of the rebels of Jerusalem against the overly powerful Roman enemy.

The extend of the Masada myth during its peak in the 1960ies and 70ies is not to be underestimated. Not only was Guttman / Yadin's mythical narrative promoted to widely accepted history and, thus, passed on to an increasing number of tourists that visited the site, but it was as well increasingly used for means of politics. The phrase "Masada shall not fall again" became a proverb for protecting the state of Israel that has become well known even outside the country. Furthermore the place and story became part of the socialization process and rituals of youth organizations and the Israeli army.

Put into the context of history it becomes clearly visible how a time of ongoing armed conflicts - the Independence War just after the foundation of the State of Israel in 1949, the Six Days war in 1966, the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the First Lebanon War in 1978 - every single one of which posed an existential threat to the nation, served as an ideal stage for the rise of a myth as powerful as the myth of Masada.

However as much as historic circumstances supported the rise of the Masada myth as much did they eventually support its fall. When in the late 1980ies, probably for the first time, durable peace seemed in reach the next generation of Israeli archaeologists set out to battle the myth and turn the mythical site of Masada into an archaeological site again. Most prominent upon this second generation is Nachman Ben-Yehuda who, like Yigael Yadin, was a fellow of Hebrew University of Jerusalem. During the post-conflict era up until the beginning of the Second Intifada in 2000 he researched both Masada and the myth that had been constructed around it.

As fast as the myth had spread in the 1960ies did it decompose in the 1990ies, when a new generation of Israelis, probably facing little identity issues as compared to their parents' generation, went out questioning not only the Masada myth. Though parts of the myth are still existent in modern Israeli society and politics parts of the population and media have forced the Masada myth out of textbooks and official rituals.

Bibliography

B.-Y. Nachman, Sacrificing truth: archaeology and the myth of Masada, Amherst 2002.

The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel, Madison 1995.

S. Guttman, With Masada, Tel Aviv 1964.

I. Steffelbauer, "War on Brigandage". Rom und der bewaffnete Widerstand in Judäa, in: Th. Kolnberger, C. Six (Ed.), Fundamentalismus und Terrorismus. Zu Geschichte und Gegenwart radikalisierter Religion, Wien 2007, 39-57.

Y. Yadin, The Excavations of Masada - 1963/64 Preliminary Report, Israel Exploration Journal 15/1-2, 1965, 1-120.

e-mail: m.pfaffl@aon.at

This article should be cited like this: M. Pfaffl, Narratives of Bravery and Fear. The Masada Myth, Forum Archaeologiae 55/VI/2010 (http://farch.net).