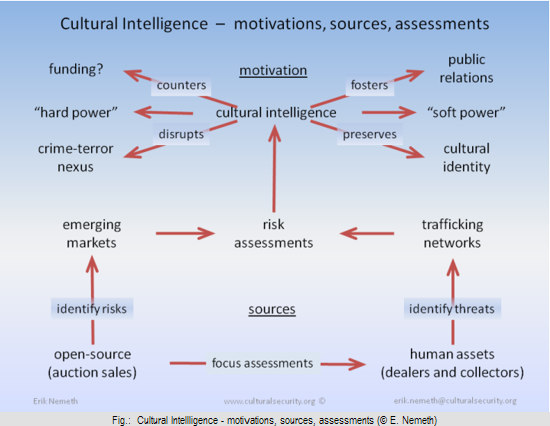

Advanced knowledge, or intelligence, on the tactical value of antiquities and cultural heritage sites enables the development of countermeasures to threats against cultural property in conflict. Intelligence on the cultural significance of monuments, the locations of collections and historic structures, the financial and political clout of antiquities, and the networks that traffic in antiquities has the potential to mitigate the tactical value exploited by non-state actors. Cultural intelligence enables tactics, or "hard power", such as: strategic bombing that minimizes collateral damage of cultural patrimony, planning for security of public collections during armed conflict, assessments for post-conflict risks of looting of archaeological sites, and enforcement of laws against trafficking. Cultural intelligence also supports pre-conflict strategic development of "soft power" such as: initiatives for complying with international conventions, planning conservation for the benefit of cultural identity, proactive repatriation and negotiation for stewardship of antiquities, and raising awareness of due diligence in collecting practices.

The clandestine nature of the art world poses challenges similar to those faced by intelligence services that collect information on foreign nations. As with foreign intelligence, open-source material provides a large portion of the raw data, and human assets facilitate access to non-public information. In the art world, open-source material includes news media that covers the art market, scholarly literature in art history and archaeology, and archives for auctions of fine art and antiquities. News media have demonstrated the potential to "predict" risks of exploitation of cultural patrimony. Prior to World War II, Alfred Barr reported on the Nazi movement to control fine art. In the 1960s, reports of looting in developing nations predated the political ramifications for collectors in market nations. In 1998, news coverage of Taliban threats to destroy the Bamiyan Buddhas "predicted" the eventual demolition in 2001.

Analysis of open-source material, such as auction archives, provides intelligence on geographic regions at risk of post- and pre-conflict looting. Comparative assessments of the market value of artworks by geographic origin aid in focusing the development of human assets in regions most at risk. Historically, governments have leveraged actors in the art world in pursuit of intelligence. During World War II, intelligence services of the Western Allied forces interrogated German dealers who had formed the networks that traded art for Nazi officials. During the Cold War, intelligence agencies actively recruited archaeologists and anthropologists who conducted field work in foreign nations of political interest. Following the models of World War II and the Cold War, security-intelligence services could engage dealers and collectors to glean insights into the clandestine art market that poses risks to cultural patrimony in conflict and into intersecting illicit markets, such as weapons, drugs, and human trafficking, that pose threats to international security.

During conflict, trafficking may provide funding to terrorist groups and thereby foster collaboration with transnational organized crime. In post-conflict, looting erodes the cultural identity of the local society and, consequently, creates a vacuum for fundamentalist ideologies. Collection and analysis of open-source material identifies targets of political violence and sites of looting in developing nations. Assets, such as antiquities dealers, aid in identifying security threats by providing information on networks for trafficking in antiquities and on intersecting networks for weapons and drugs. In combination, open-source collection and human assets provide data for risk assessments. The resulting intelligence enables countermeasures to looting and fosters public relations. By contributing to the disruption of trafficking and the preservation of cultural identity, cultural intelligence becomes a source of both hard power in countering collaboration between organized crime and terrorist groups and soft power in garnering political goodwill in regions of conflict.

![]() © Erik Nemeth

© Erik Nemeth

e-mail: erik.nemeth@culturalsecurity.org

This article should be cited like this: E. Nemeth, The Art of Cultural Intelligence: intelligence for countering threats to cultural property in conflict, Forum Archaeologiae 55/VI/2010 (http://farch.net).