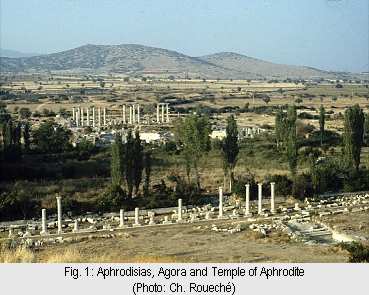

The New York University excavation at Aphrodisias in Caria (fig. 1-2) is one of the largest explorations of a Roman site to have been started since the end of the Second World War. The site is peculiarly rich, both because it has remained undisturbed for so long, and also because the wealth of the local community could be lavishly expressed by exploiting the local marble - quarried only a few kilometres from the city. Over a relatively short period, therefore, since the excavations commenced in 1961, a very great deal of material has been uncovered, and recorded with increasingly modern methods:

The New York University excavation at Aphrodisias in Caria (fig. 1-2) is one of the largest explorations of a Roman site to have been started since the end of the Second World War. The site is peculiarly rich, both because it has remained undisturbed for so long, and also because the wealth of the local community could be lavishly expressed by exploiting the local marble - quarried only a few kilometres from the city. Over a relatively short period, therefore, since the excavations commenced in 1961, a very great deal of material has been uncovered, and recorded with increasingly modern methods:see http://www.nyu.edu/projects/aphrodisias/

The site has long been known for its remarkable marble sculpture, and also for its abundant inscriptions. In modern times, inscriptions have been recorded at the site since 1705; since 1966 Joyce Reynolds with (from 1970) Charlotte Roueché and (since 1995) Angelos Chaniotis have been working on the inscriptions. For the history of the texts from the site see:

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/AphEpig.htm

We now have records of some 1000 inscribed texts, or fragments of texts; and the majority have been recorded in considerable detail, with abundant photographs and a good deal of archaeological information. While some categories of inscriptions have already been published, the challenge confronting us is to present the body of the material, as a coherent whole, exploiting the very rich data which we possess. The primary problem, therefore, is one of volume: any printed book would be unmanageably large - and expensive - or have to omit a great deal of data. We therefore started to explore the

Digression: What is Mark-up? What is semantic Mark-up?

Please skip the following very simplistic description if you already know the answer!

Experienced readers may return here!

There are still issues and problems that we have not yet resolved with our electronic publication format and the EpiDoc recommendations; the work is ongoing. The requirements of epigraphic documents are so broad that only when we began to mark-up the texts in this project did many unforeseen issues come to light. In order to develop further and cater for the wide range of epigraphic texts and projects, the recommendations need to be tested and used by more scholars working in the field. This will be a developing project for some time.

possibilities of digital publishing. Ten years ago, it looked as if this would mean publishing a CD-ROM; but that would still severely curtail the use of images. But it was only in 2000 that Charlotte Roueché was awarded a Research Readership by the British Academy in order to tackle the problem - and by then it was already clear that publication on the World Wide Web was a serious and realistic possibility.

possibilities of digital publishing. Ten years ago, it looked as if this would mean publishing a CD-ROM; but that would still severely curtail the use of images. But it was only in 2000 that Charlotte Roueché was awarded a Research Readership by the British Academy in order to tackle the problem - and by then it was already clear that publication on the World Wide Web was a serious and realistic possibility.

Since September 2000, therefore, I have been working on this project. In October 2000 I established contact with Tom Elliott, of the University of North Carolina, who was setting up the EpiDoc project (web-site at http://www.unc.edu/awmc/epidoc/) which is described further below.

We decided to test the feasibility of the project by undertaking a relatively small task - the republication, in digital form, of Roueché's Aphrodisias in Late Antiquity, first published by the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies in 1989, and now out of print. This involves publishing less than 250 texts and there are some new texts to be added, as well as corrections to be made, which ensured that there will be some academic value to the republication. We applied to the Leverhulme Trust for a Research Interchange Grant, which enabled us to appoint a research assistant, Gabriel Bodard in October 2001. Since then we have been working intensively on the project.

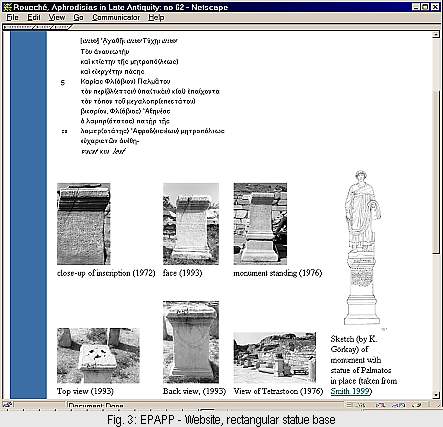

On the epigraphic side, various interesting points have emerged. Firstly, presenting the material in this way enables - in fact forces - the scholar to observe the interrelationship between text, and monument. It is no longer possible simply to give text http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/images/deering/Deering_06v.jpg with no indication of the nature of the support. Instead, the text is presented with its support: and, because there is no limitation on the illustration, it is possible to offer, not only a close up picture of the text, but also images of the support as a monument - its back and sides, or an accompanying statue (fig. 3): http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/ALA_062.htm

This raises some interesting issues when one support has more than one text: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/ALA_022.htm

we are still discussing how best this should be expressed.

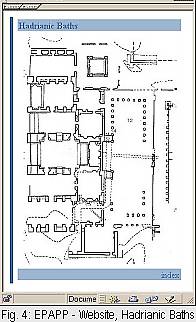

Furthermore, it becomes far easier to express the position of a stone, with a simple link to a site-plan (fig. 4): http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/baths.htm

Furthermore, it becomes far easier to express the position of a stone, with a simple link to a site-plan (fig. 4): http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/examples/baths.htm

This is perhaps of particular interest with Late Antique material, when often a high proportion of the material is still in situ.

A feature which I had not anticipated concerns the earlier copies of some inscriptions. We happened to have been given, by the late Madame Jeanne Robert, the pages of a notebook kept by John Deering (later Gandy-Deering) who visited the site in 1813. We have scanned these, and created a dossier, which can be used as it stands: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/cch/epapp/examples/deering/contents.html

but which can also be accessed from the publication of the relevant inscription. This will be particularly important in the case of those texts which have not been found again; it also helps to make accessible material

which it is not always easy to find.

One advantage of this particular project, as a pilot, is that it will be possible to compare the finished product with the conventional book which preceded it. I have been working on the narrative portion of the publication - which needs to give coherence to the documents even more than when that coherence is provided by the physical location. This is one of many new aspects to this project.

Anyone who has published anything has -whether they knew it or not - marked up a document. For example, we used, in the days of typewriters, to underline words we wanted in italic, and put a wiggly line under words to go in bold: we still do that on proofs. When we moved to word-processors, some of this was done for us: we could put words into italic and bold ourselves. But in fact we were still 'marking up' the document: we had entered (invisible) instructions to the machine to say that this was what we wanted it to do.

We have all lived with the frustrations which come when a computer strips out those instructions: you send a document to someone and the bold and italic disappear. It was to stop this happening on the Internet that HTML was developed: this is a mark-up language, a series of instructions about how a document should be presented. It was developed under the auspices of the non-profit making World Wide Web Consortium, and all browsers - whoever manufactures them - adhere to its standards. In consequence what appears in bold in Netscape on my Macintosh also appears in bold in Explorer on your PC.

To achieve this result, commands, in HTML (Hyper-Text Mark-up Language), are inserted into the document: 'this is to be bold', 'this is were bold stops'. If you see it all written out, it looks very complicated and off-putting; but there is plenty of software which allows you just to press the relevant key to give the instruction bold/not bold.

HTML offers a series of commands which determine the appearance of a document, just as we always used to do. But once you have accepted the concept of embedding this sort of information in a document, there is actually no reason why such information should be limited to issues of display. XML - Extensible Mark-up Language - also designed by the World Wide Web Consortium, offers the chance to enter semantic information. That is, instead of saying 'the next three words are in italic', you can enter the instruction 'the next three words are a book title'. After that, you can apply a style sheet which says - 'in this publication, I want all book titles to be in italic' or one which says 'I want all book titles to be in capitals'. You can also say 'I want a list of all book titles' or 'Look for the word Queen in all book titles'.

This is therefore a very powerful tool, with great potential. As with HTML, you don't have to wrestle with the detail; there is software which will enable you to give your commands, although clearly there is a far more complex range of commands to be given. It can be used to prepare text for publication either in book or in electronic form. It is in some ways particularly appropriate for the publication of papyri and inscriptions, where we already have quite a lot of extra information in our documents: we have signs which say: 'the following is not visible, but is my guess' or 'the following is erased' or 'I have added the following letter'. We are therefore already in the habit of marking up our texts very extensively, because we are trying to convey information about a text and its physical condition at the same time.

There is therefore a natural intellectual process at work if we start to use XML to convey this information, and perhaps other information too.

As has been said above, the late antique Aphrodisias material is being used to pilot EpiDoc, a new approach to the presentation and publication of epigraphic texts. This approach, which is based on the TEI recommendations (see below), is developing standards which take into account the unique qualities and requirements of ancient texts and manuscripts, and allow them to be made available via the internet in a useful and meaningful form. An inscription can be published, as can any other category of text, an instruction manual or a novel, but we need conventions and standards for texts published by different scholars or projects to be compatible with one another. It should be stressed that these standards enable compatibility of documents without imposing structure, layout, or intellectual content on individual projects.

In summary, the project employs the following tools and standards:

With the help of the Leverhulme grant, we have already held one workshop at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and we are currently planning another for London in July; see Calendar at

http://www.kcl.ac.uk/humanities/cch/epapp/epapp.htm

We also hope to present our material at the International Epigraphic Congress in Barcelona, 3-8 September 2002

http://www.ub.es/epigraphiae/

We very much hope that the work which we are doing will produce a useful tool which can be used and refined by other colleagues in the field of epigraphy. We would like to invite contributions and expressions of interest from epigraphers, papyrologists, and other classical scholars.

e-mail: charlotte.roueche@kcl.ac.uk

gabriel.bodard@kcl.ac.uk

This article will be quoted by G. Bodard - Ch. Roueché,

The Epidoc Aphrodisias Pilot Project, Forum Archaeologiae 23/VI/2002 (http://farch.net).